By Alison Snieckus.

When Princeton Learning Cooperative members move on from PLC, into college, work, and life generally, they nearly always express how much their mentoring relationship has helped and supported them as they forged their path through opportunities and offerings. Mentoring is without a doubt the part of the “PLC magic” that we most value. It’s more important than just about everything.

The first step to good mentoring is to reserve space for the relationship between mentor and mentee to develop. With that in mind, we schedule weekly meetings with our mentees and overtly offer that time each week. It’s the young person’s choice if they want to come to the meeting, and most do–but if not, we ask them again the following week. We use the meetings to help the member keep on track with what they want to do in life, to reflect on choices made and actions taken, to offer opportunities that fit with their goals, to discuss any issues that have come up, to explore the intersections of our lives, and occasionally to challenge them to look realistically at how their day-to-day choices match up with the dreams they have for themselves.

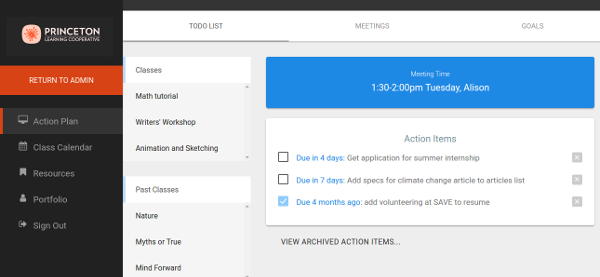

At PLC, each member has an online portfolio in a system designed specifically for young people who are self-directing their educations, which includes functions to support mentoring in particular. We record notes during each mentoring meeting, specify short- and long-term goals and action items, store links to resources that the young person is using in their learning, and document the various classes, projects and activities they are engaged in. The portfolio grows and deepens as the young person’s education develops, reflecting their interests, abilities, and sometimes a dream come true. Here’s a printscreen of the main Action Plan page, showing tabs for todo list (shown), meetings, and goals:

Although the concept of mentoring has a long history—“Mentor” was the name of a friend of Odysseus who was entrusted with the education of his son—and many people can point to a mentor in their lives who served a critical role, mentoring is not seen as a key element in our modern day education system. But I wonder if that’s a change in the works. There have been a number of important studies in the last few years that tout the positive, life-affirming effects on young people when they have access to a mentor. The Mentoring Effect (2014), a report summarizing a survey of 1,109 18- to 21-year-olds about their experiences with both naturally-occurring and formal mentoring relationships, concludes that “ structured and naturally occurring mentoring relationships have powerful effects which provide young people with positive and complementary benefits in a variety of personal, academic, and professional factors.” The report offers a number of specifics:

- Young adults who had both formal and informal mentoring speak highly of these relationships, saying that the mentors help them keep on track and make good choices. Over 90% rate the experience as “helpful”, with over 50% rating it as “very helpful”.

- Longer-term mentoring relationships (more than a year) have greater value for youth; the number of youth who rated the relationship as “very helpful” doubled when comparing relationships that were more than one year (67%) to less than one year (33%).

- 86% of young people who had mentors, both formal and informal, expressed a desire to become a mentor, which both endorses the role of the mentor and the young person’s desire to contribute to the world around them.

Surprisingly, we haven’t always had mentoring at PLC as a defined part of our program. When we were just getting started with only a handful of members, it was easy to get to know each other, to be helpful in the moment, to develop deep relationships with each other. But as we outgrew our original one-room space at the Princeton Arts Council, we decided that each member should have a go-to staff person, a “mentor” that would help them make choices about their education and how they were spending their time now that they weren’t in school or homeschooling with their parents.

In 2011, there was no roadmap, no instructor’s manual on how to set up a mentoring program, so we looked to the few examples we could find and started figuring it out. We decided that weekly meetings with mentees made the most sense and went about assigning each member to a staff person. We cobbled together a rudimentary system to keep track of our meetings and then set to the task of getting to know our mentees. It was clear right away that the weekly meetings and documentation were effective and useful. But we didn’t yet realize the deep importance of mentoring.

A few months back I wrote about a study that identified five key actions that adults can take that help young people learn, grow, and thrive. The evidence is mounting as to the positive effects of mentoring, of taking the time to develop deep, caring relationships between young people and knowledgeable adults. Share this Post